Sunday, October 30, 2005

Jeff Vandermeer on Vanderworld has started a Halloween Haiku competition. It is definitely worth a look...

Friday, October 28, 2005

Shallowlands - Ros Barber's blog

Some time ago I blogged about the rather excellent poet Ros Barber of whom I am big fan. I am pleased to report she has started a blog called Shallowlands about writing a novel. It is entertaining and very interesting and I shall be dipping in to see how she is getting on.

Thursday, October 27, 2005

'Contexts' in 'The Writers World'

On Tuesday I was contacted by a student, Angi Holden, who is studying Creative Writing at Manchester Metropolitan University in Alsager. Apparently part of the course is called 'Contexts' and she has a presentation assignment on 'The Writer's World' and has decided to focus on Chester Litfest. She asked me a few interesting questions. Here they are with my responses.

A.H: What is the value of a festival - such as Chester Litfest - to an established writer?

C.D: First of all not sure about the 'established writer' bit, really. I've only written three novels, I don't think that's 'established' really. But for a writer like me, the main value of any Litfest (and I've performed several this year - WOW (Writing on the Wall at Liverpool), Swindon, Basingstoke, Cheltenham and now Chester) is to introduce myself to potential readers. They do tend to be potential readers rather than actual readers because apart from my friends in Chester, few people have come across my work even though it has been quite widely reviewed. And because I am relatively unknown my talks have to be on topics that I think might interest people and so they will come to find out about the subject rather than come just to 'meet the author' as they do for well-known novelists. Well-known novelists tend to talk about things like how they write, how they got started i.e. general things about their lives as writers. My talks tend to be less about me and more about the topic of my research. At the end of my talk I hope they are interested enough to want to buy my book, and then buy any subsequent books that I write. Quite often they don't, of course - my talk has given them all the information they need - and that is good as well, because part of the reason I've written my books is to tell people about characters or events which I think are interesting, important and deserve wider attention, and so just their attendance at my talk achieves this aim.

Another benefit of being in a festival is that even if people don't come to your event they read about you in the programme which is widely circulated so that is good publicity.

Sometimes local bookshops stock festival books so that can be of benefit too - because sometimes it is hard to even get your books in bookshops. So being in a festival helps to bring your book to the attention of bookshop managers - for example in Swindon the manager at Waterstones there read my book because I was coming to the festival and liked it so much she made it her recommended read and put it on display which would more or less guarantee that it would sell. However it does depend on the manager - at Basingstoke the bookshop associated with the festival didn't stock my book which was disappointing.

The big festivals have an extra benefit in that you meet other writers and journalists. In Cheltenham I met several well-known authors and a journalist from the Times asked me a few questions. They also treat their writers really well, and it is great to be invited.

All festivals are a lot of fun too, and I really enjoy them but they are exhausting because after travelling for several hours with, in my case, a computer, a bag full of books, and an overnight bag you then have to set everything up and perform then either sleep badly in a B&B or make the long journey back again. And of course I have to spend several days beforehand preparing my talk with pictures and words. I enjoy this too, but all of this takes you away from writing, and it is impossible to write before or after giving talks - even Alan Bennett says so.

A.H: How does it compare with your perceptions of a literary festival from a "punters" point of view?

C.D: From the punters point of view ... well, I've been to as many events as I can in the Chester Festival (as I do every year) to support both the festival and the people involved. There were more I would have liked to have gone to but I was away at festivals myself so I couldn't. I would have liked to have gone to Joanne Harris's and David Frost's too, and I should have liked to have gone to Chester Poets' but was away at events. I suppose, like you, I like to hear about other writers' lives and how they got started and it is always interesting to hear the writers' real voice and see how it compares to the one on the page. I also like to support local writers and writers I have never heard of before - and these often turn out to give the best events - the most interesting and informative.

A.H: What's been your highlight of the festival?

C.D: So far the best event of this year for me was the one at Chester University by a couple of lecturers there (John Cartwright and Brian Baker). They have written a book about science in literature and their lectures were fascinating. One was on how writers have mentioned science in literature through the ages and the other on science fiction.

A.H: What is the value of a festival - such as Chester Litfest - to an established writer?

C.D: First of all not sure about the 'established writer' bit, really. I've only written three novels, I don't think that's 'established' really. But for a writer like me, the main value of any Litfest (and I've performed several this year - WOW (Writing on the Wall at Liverpool), Swindon, Basingstoke, Cheltenham and now Chester) is to introduce myself to potential readers. They do tend to be potential readers rather than actual readers because apart from my friends in Chester, few people have come across my work even though it has been quite widely reviewed. And because I am relatively unknown my talks have to be on topics that I think might interest people and so they will come to find out about the subject rather than come just to 'meet the author' as they do for well-known novelists. Well-known novelists tend to talk about things like how they write, how they got started i.e. general things about their lives as writers. My talks tend to be less about me and more about the topic of my research. At the end of my talk I hope they are interested enough to want to buy my book, and then buy any subsequent books that I write. Quite often they don't, of course - my talk has given them all the information they need - and that is good as well, because part of the reason I've written my books is to tell people about characters or events which I think are interesting, important and deserve wider attention, and so just their attendance at my talk achieves this aim.

Another benefit of being in a festival is that even if people don't come to your event they read about you in the programme which is widely circulated so that is good publicity.

Sometimes local bookshops stock festival books so that can be of benefit too - because sometimes it is hard to even get your books in bookshops. So being in a festival helps to bring your book to the attention of bookshop managers - for example in Swindon the manager at Waterstones there read my book because I was coming to the festival and liked it so much she made it her recommended read and put it on display which would more or less guarantee that it would sell. However it does depend on the manager - at Basingstoke the bookshop associated with the festival didn't stock my book which was disappointing.

The big festivals have an extra benefit in that you meet other writers and journalists. In Cheltenham I met several well-known authors and a journalist from the Times asked me a few questions. They also treat their writers really well, and it is great to be invited.

All festivals are a lot of fun too, and I really enjoy them but they are exhausting because after travelling for several hours with, in my case, a computer, a bag full of books, and an overnight bag you then have to set everything up and perform then either sleep badly in a B&B or make the long journey back again. And of course I have to spend several days beforehand preparing my talk with pictures and words. I enjoy this too, but all of this takes you away from writing, and it is impossible to write before or after giving talks - even Alan Bennett says so.

A.H: How does it compare with your perceptions of a literary festival from a "punters" point of view?

C.D: From the punters point of view ... well, I've been to as many events as I can in the Chester Festival (as I do every year) to support both the festival and the people involved. There were more I would have liked to have gone to but I was away at festivals myself so I couldn't. I would have liked to have gone to Joanne Harris's and David Frost's too, and I should have liked to have gone to Chester Poets' but was away at events. I suppose, like you, I like to hear about other writers' lives and how they got started and it is always interesting to hear the writers' real voice and see how it compares to the one on the page. I also like to support local writers and writers I have never heard of before - and these often turn out to give the best events - the most interesting and informative.

A.H: What's been your highlight of the festival?

C.D: So far the best event of this year for me was the one at Chester University by a couple of lecturers there (John Cartwright and Brian Baker). They have written a book about science in literature and their lectures were fascinating. One was on how writers have mentioned science in literature through the ages and the other on science fiction.

Tuesday, October 25, 2005

Talk at the Chester Literature Festival.

It is the last week of the Chester Literature Festival and my last event for a while - a talk on THE MAKING OF MODERN MADNESS at the Grosvenor Museum. It was good to be on home territory with a room full of people who have read my book and know me and I was very glad to see them. I don't feel like giving up any more.

It is the last week of the Chester Literature Festival and my last event for a while - a talk on THE MAKING OF MODERN MADNESS at the Grosvenor Museum. It was good to be on home territory with a room full of people who have read my book and know me and I was very glad to see them. I don't feel like giving up any more. Jan Bengree gave me an excellent introduction, and Sheila Parry gave the vote of thanks. Sheila's Steve operated the computer very well, and when the projector gave up half way through (because it wasn't having enough attention) he managed to cajole it into working again. Alan Wall was there, which was very good of him because he lives far away, and the manager of Waterstones sold my books - and amazingly some people bought them.

Tonight I feel all is not lost and tomorrow I am going to work hard and try to produce another book if I can.

Monday, October 24, 2005

Heaton Chapel Lit and Phil

It was a dark and windy night - a wet one too - but through the dirty diamond windows a faint glimmer showed...

Rows and rows of chairs - surely they won't need all those...

But this is the Heaton Chapel Lit and Phil - second oldest Lit and Phil in the country and they have standards to uphold...

And they kept coming and a coming..

And they kept coming and a coming..

.

Until there were many...

Jolly good audience, very appreciative, and lovely lot of people. They'd never heard of Alfred Wegener but they have now.

The evening, however was not without incident. The projector seemed to be dead at first and four of us stared at it until it got embarrassed and started to work, spontaneously...and on the way back I decided to go round the traffic roundabout using the unique Hodmandod anticlockwise system. As experiments go it was unsuccessful and I only just escaped with my life.

Rows and rows of chairs - surely they won't need all those...

But this is the Heaton Chapel Lit and Phil - second oldest Lit and Phil in the country and they have standards to uphold...

And they kept coming and a coming..

And they kept coming and a coming...

Until there were many...

Jolly good audience, very appreciative, and lovely lot of people. They'd never heard of Alfred Wegener but they have now.

The evening, however was not without incident. The projector seemed to be dead at first and four of us stared at it until it got embarrassed and started to work, spontaneously...and on the way back I decided to go round the traffic roundabout using the unique Hodmandod anticlockwise system. As experiments go it was unsuccessful and I only just escaped with my life.

Saturday, October 22, 2005

The Mimosa Festival

Well after a week the blog is back - I missed it too much.

Today I went to the Bethel Presbyterian Church of Wales in Liverpool. I walked down Penny Lane (as in the song) and it was litter-strewn and run-down looking, especially the millennium park which was particularly bleak. The Welsh chapel stood proud of the hill, instantly recognisable - that characteristic combination of austerity overlain with dour ornament. Inside there was another country - Wales in England, people coming up to me talking a language I should know but don't. They were my height, my complexion, my people, all of us from the same stock - Romano-Celt. For an hour I listened to the language that should be mine, but isn't, the language I was used to hearing as a child on holiday but never learnt: Gareth James and his talk entitled 'Cefndir y Mimosa'. The sparse snatches I understood sounded very interesting and not for the first time I wished there was some sort of hat you could wear, the universal translator that is always so freely available in most works of science-fiction. But then there was a talk in English which I know was fascinating - author Susan Wilkinson from Toronto talking about 'The Romance of the Mimosa'. The Mimosa was a ship that began life as a tea clipper but is most famous for being the ship that transported about 160 Welsh people to Patagonia. They left from Liverpool. At the time 80 000 people out of a total population of 450 000 were Welsh in Liverpool and there were 70 Welsh chapels in the city. Bethel is one of just seven that remain and is due to be demolished in the near future. Like much of the rest of the Welsh legacy in Liverpool it is crumbling away, is in desperate need of expensive refurbishment and is under-used. However the Welsh community in Liverpool is live and kicking and still publishing.

Today I went to the Bethel Presbyterian Church of Wales in Liverpool. I walked down Penny Lane (as in the song) and it was litter-strewn and run-down looking, especially the millennium park which was particularly bleak. The Welsh chapel stood proud of the hill, instantly recognisable - that characteristic combination of austerity overlain with dour ornament. Inside there was another country - Wales in England, people coming up to me talking a language I should know but don't. They were my height, my complexion, my people, all of us from the same stock - Romano-Celt. For an hour I listened to the language that should be mine, but isn't, the language I was used to hearing as a child on holiday but never learnt: Gareth James and his talk entitled 'Cefndir y Mimosa'. The sparse snatches I understood sounded very interesting and not for the first time I wished there was some sort of hat you could wear, the universal translator that is always so freely available in most works of science-fiction. But then there was a talk in English which I know was fascinating - author Susan Wilkinson from Toronto talking about 'The Romance of the Mimosa'. The Mimosa was a ship that began life as a tea clipper but is most famous for being the ship that transported about 160 Welsh people to Patagonia. They left from Liverpool. At the time 80 000 people out of a total population of 450 000 were Welsh in Liverpool and there were 70 Welsh chapels in the city. Bethel is one of just seven that remain and is due to be demolished in the near future. Like much of the rest of the Welsh legacy in Liverpool it is crumbling away, is in desperate need of expensive refurbishment and is under-used. However the Welsh community in Liverpool is live and kicking and still publishing.

THE WELSH OF MERSEYSIDE is one of their recent publications. It is well-researched and contains a catalogue of Welsh buildings and characters including one John Davies 'Cadvan'. He was a 'cantakerous' competitor in the National Eisteddfod (a Welsh cultural festival). Although his heroic verse won first prize in the 1884 competition his love lyrics in the 1900 competition were not similarly lauded and he protested vehemently. He stares out of the pages of this book - a handsome man but clearly eccentric - his Wesleyan Methodist ministerial robes festooned with eleven medals dispersed over the entire expanse of his chest.

THE WELSH OF MERSEYSIDE is one of their recent publications. It is well-researched and contains a catalogue of Welsh buildings and characters including one John Davies 'Cadvan'. He was a 'cantakerous' competitor in the National Eisteddfod (a Welsh cultural festival). Although his heroic verse won first prize in the 1884 competition his love lyrics in the 1900 competition were not similarly lauded and he protested vehemently. He stares out of the pages of this book - a handsome man but clearly eccentric - his Wesleyan Methodist ministerial robes festooned with eleven medals dispersed over the entire expanse of his chest.

Today I went to the Bethel Presbyterian Church of Wales in Liverpool. I walked down Penny Lane (as in the song) and it was litter-strewn and run-down looking, especially the millennium park which was particularly bleak. The Welsh chapel stood proud of the hill, instantly recognisable - that characteristic combination of austerity overlain with dour ornament. Inside there was another country - Wales in England, people coming up to me talking a language I should know but don't. They were my height, my complexion, my people, all of us from the same stock - Romano-Celt. For an hour I listened to the language that should be mine, but isn't, the language I was used to hearing as a child on holiday but never learnt: Gareth James and his talk entitled 'Cefndir y Mimosa'. The sparse snatches I understood sounded very interesting and not for the first time I wished there was some sort of hat you could wear, the universal translator that is always so freely available in most works of science-fiction. But then there was a talk in English which I know was fascinating - author Susan Wilkinson from Toronto talking about 'The Romance of the Mimosa'. The Mimosa was a ship that began life as a tea clipper but is most famous for being the ship that transported about 160 Welsh people to Patagonia. They left from Liverpool. At the time 80 000 people out of a total population of 450 000 were Welsh in Liverpool and there were 70 Welsh chapels in the city. Bethel is one of just seven that remain and is due to be demolished in the near future. Like much of the rest of the Welsh legacy in Liverpool it is crumbling away, is in desperate need of expensive refurbishment and is under-used. However the Welsh community in Liverpool is live and kicking and still publishing.

Today I went to the Bethel Presbyterian Church of Wales in Liverpool. I walked down Penny Lane (as in the song) and it was litter-strewn and run-down looking, especially the millennium park which was particularly bleak. The Welsh chapel stood proud of the hill, instantly recognisable - that characteristic combination of austerity overlain with dour ornament. Inside there was another country - Wales in England, people coming up to me talking a language I should know but don't. They were my height, my complexion, my people, all of us from the same stock - Romano-Celt. For an hour I listened to the language that should be mine, but isn't, the language I was used to hearing as a child on holiday but never learnt: Gareth James and his talk entitled 'Cefndir y Mimosa'. The sparse snatches I understood sounded very interesting and not for the first time I wished there was some sort of hat you could wear, the universal translator that is always so freely available in most works of science-fiction. But then there was a talk in English which I know was fascinating - author Susan Wilkinson from Toronto talking about 'The Romance of the Mimosa'. The Mimosa was a ship that began life as a tea clipper but is most famous for being the ship that transported about 160 Welsh people to Patagonia. They left from Liverpool. At the time 80 000 people out of a total population of 450 000 were Welsh in Liverpool and there were 70 Welsh chapels in the city. Bethel is one of just seven that remain and is due to be demolished in the near future. Like much of the rest of the Welsh legacy in Liverpool it is crumbling away, is in desperate need of expensive refurbishment and is under-used. However the Welsh community in Liverpool is live and kicking and still publishing.  THE WELSH OF MERSEYSIDE is one of their recent publications. It is well-researched and contains a catalogue of Welsh buildings and characters including one John Davies 'Cadvan'. He was a 'cantakerous' competitor in the National Eisteddfod (a Welsh cultural festival). Although his heroic verse won first prize in the 1884 competition his love lyrics in the 1900 competition were not similarly lauded and he protested vehemently. He stares out of the pages of this book - a handsome man but clearly eccentric - his Wesleyan Methodist ministerial robes festooned with eleven medals dispersed over the entire expanse of his chest.

THE WELSH OF MERSEYSIDE is one of their recent publications. It is well-researched and contains a catalogue of Welsh buildings and characters including one John Davies 'Cadvan'. He was a 'cantakerous' competitor in the National Eisteddfod (a Welsh cultural festival). Although his heroic verse won first prize in the 1884 competition his love lyrics in the 1900 competition were not similarly lauded and he protested vehemently. He stares out of the pages of this book - a handsome man but clearly eccentric - his Wesleyan Methodist ministerial robes festooned with eleven medals dispersed over the entire expanse of his chest.

Sunday, October 16, 2005

MRS MOUNTER - A Poem

I am going to finish my blog for a while...but before I go...

A few nights ago I went to see two poets - Fleur Adcock and Wendy Cope who were funny and at the same time made you see things in a different light. It was a good evening.

So to finish this literary blog - at least for now - here is a poem I wrote about ten years ago. It is about Mrs Mounter - a painting by Harold Gilman. She was his landlady and he painted her several times. I think she looks like she is remembering back to when she was younger.

MRS MOUNTER

Two cups, two spoons, two saucers,

shoved together anyhow.

Which one of us is chipped, stirs

nothing, an empty cup? How

can I know it's not just you

that's fading away, wearing

out? I am watered down too,

but remember the longing

to see something more than tea

in your black eyes - the promise

of rich, over-brewed love, we

both once drank instead of this.

A few nights ago I went to see two poets - Fleur Adcock and Wendy Cope who were funny and at the same time made you see things in a different light. It was a good evening.

So to finish this literary blog - at least for now - here is a poem I wrote about ten years ago. It is about Mrs Mounter - a painting by Harold Gilman. She was his landlady and he painted her several times. I think she looks like she is remembering back to when she was younger.

MRS MOUNTER

Two cups, two spoons, two saucers,

shoved together anyhow.

Which one of us is chipped, stirs

nothing, an empty cup? How

can I know it's not just you

that's fading away, wearing

out? I am watered down too,

but remember the longing

to see something more than tea

in your black eyes - the promise

of rich, over-brewed love, we

both once drank instead of this.

Thursday, October 13, 2005

Margaret Murphy

Now for a real crime writer - Margaret Murphy - who lives close by on Wirral and as well as being a great teacher and speaker writes highly entertaining crime novels with local settings. She has written two based in Chester itself (DARKNESS FALLS and WEAVING SHADOWS) and I find it great fun to pick out the places you know. However her latest trilogy (first is the DISPOSSESSED and the second is out in November (NOW YOU SEE ME)) is based in the more exciting city of Liverpool because, after all, Chester is a place where little tends to happen - although in Margaret's two novels about the place, things are certainly very lively indeed and they are great page turners.

Now for a real crime writer - Margaret Murphy - who lives close by on Wirral and as well as being a great teacher and speaker writes highly entertaining crime novels with local settings. She has written two based in Chester itself (DARKNESS FALLS and WEAVING SHADOWS) and I find it great fun to pick out the places you know. However her latest trilogy (first is the DISPOSSESSED and the second is out in November (NOW YOU SEE ME)) is based in the more exciting city of Liverpool because, after all, Chester is a place where little tends to happen - although in Margaret's two novels about the place, things are certainly very lively indeed and they are great page turners.

She has an excellent website (link above and below) which gives a lot of information about the books with extracts. She has kindly answered my seven questions.

1.Do you have any connection with snails? (or anecdotes, memorable encounters..etc.)

I kept pet snails, in junior school. I've always hated slugs, though. Later, when I taught biology, I kept giant African snails - this was before Health and Safety banned everything, on the basis it might be unhygienic.

2. What is your proudest moment?

I come from a repressed Roman Catholic background, where Pride (capital P) was a sin, and always came before a fall. I do have moments when I'm quietly pleased, in an 'aw shucks' kind of way: like having my first book published. Or having my next book published. Positive feedback from fans pleases me more than anything, though.

3. Have you ever had a life-changing event - if so what was it?

1989 - 1990. I had a series of TIAs. I lost concentration, co-ordination and had trouble articulating. Problematic for a teacher, and devastating for someone who always loved language. As I began to recover, I decided I'd made enough excuses: I had to try to write that book I'd always said I would write. So began my career as a novelist.

4. What is the saddest thing you’ve ever heard of or seen?

A good friend - a refugee - experiencing a flashback. I was caring for her after a particularly traumatic interview, and she woke from a nightmare, and thought she was back in prison. When she looked at me, she saw the soldiers coming to attack her again.

5. If there was one thing you’d change about yourself what would it be?

I'd like to have more energy, so I could get more done with the day.

6. What is happiness?

Deep, Clare, really deep... Happiness used to be a cigar called Hamlet, apparently, but never having been a smoker, I can't vouch for that. Happiness is waking in the morning with the sound of the birds outside the window, the sun already warming the garden, and the scent of honeysuckle lingering in the air.

It's the first thrill of excitement as you begin planning a new novel. It's sharing a bottle of cold wine on a summer's evening with an old friend. Your voice and theirs no more than a murmur on the clove-scented air.

7. What is the first thing you do when you get up?

I open the bedroom curtains and see what kind of day it is. Then I drink lots and lots of tea.

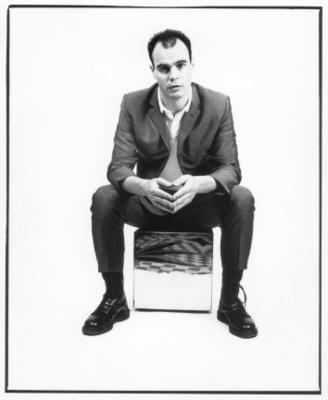

Jake Arnott and THE LONG FIRM

Jake Arnott has written three loosely connected novels about criminals - THE LONG FIRM, HE KILLS COPPERS and TRUE CRIME. - all very successful and well-reviewed. THE LONG FIRM has been made into an acclaimed series for BBCTV. On the 18th October he too is giving a talk in Chester - this time on violence in the novel. Judging from his responses to my interview it should be very interesting.

First I shall review THE LONG FIRM (which I do not think contains spoilers but the interview follows after the photograph).

THE LONG FIRM by Jake Arnott

THE LONG FIRM is about crime but is not really a crime novel, it could be accurately described as a character study of a man who happens to be a criminal - ‘A Torture Gang Boss’ in fact who lives alongside the Kray twins in 1960s London. The Kray twins are not the only nonfictional characters who take a bit-part in this book: others are Judy Garland, Dorothy Squires, Johhnnie Ray, Mickey Deans, all of them portrayed as washed up and unsavoury characters - sad people clinging onto life through a haze of drugs and alcohol.

THE LONG FIRM is about crime but is not really a crime novel, it could be accurately described as a character study of a man who happens to be a criminal - ‘A Torture Gang Boss’ in fact who lives alongside the Kray twins in 1960s London. The Kray twins are not the only nonfictional characters who take a bit-part in this book: others are Judy Garland, Dorothy Squires, Johhnnie Ray, Mickey Deans, all of them portrayed as washed up and unsavoury characters - sad people clinging onto life through a haze of drugs and alcohol.

A large part of the adult life of Harry Starks is revealed through five people who are intimately involved with him: Terry, a young male prostitute and one-time boyfriend who escapes Starks’s clutches after being tortured with a red-hot poker in the mouth; another homosexual Lord Thursby who becomes involved in Starks’s dodgy business activities in a part of Africa; Jack the Hat, a heterosexual accomplice; Ruby a faded starlet who becomes Starks’s go-between with a corrupt policeman and finally Lenny who is a university lecturer and criminologist and is responsible for Starks’s interest in education once he is incarcerated in jail. Each of these people is corrupted by Starks, each one is tortured physically or mentally until they are forced to kill or torture others. Starks is charismatic, preys on those weaker than he is, which is just about everyone.

There is a lot of sex and violence in this novel. The first sex scene is on page seven. It is cursory, unemotional, it is only later on in the book that a couple of homosexual orgies are described in graphic detail. Starks is a homosexual (‘not gay’ he declares towards the end of the book) and one of the few things that disturbs him is the death of a young homosexual called Bernie. He is also Jewish, though this seems to have little bearing on his character, and a manic depressive - given to black periods when he retires to listen to recordings of Winston Churchill and punish the young men who love him. Harry Starks is overwhelmingly cruel and forces subjugation on anyone that comes close. The way he does this is convincing and extremely chilling.

Each of the characters in the novel has a distinctive voice. Terry’s is wheedling - unsurprising since he is in the middle of being physically abused. The Lord’s account is written in a diary form, which is quite pompous, while Jack the Hat’s is written in a fast-paced staccato. It is this voice I found the most sympathetic - Jack the Hat has motivation, some endearing qualities, weaknesses, a sense of guilt which were abjectly missing from any ot the other accounts. He is the one who doesn’t last. It is as if by showing weakness he condemns himself to an early death. Ruby’s account is written in a summarily fashion. She tells us how she feels about things rather than shows us; while Terry’s style is so full of jargon and correct-thinking it borders on the humorous and for a time is tongue in cheek - and I have to say I do know people who talk like that, so it is, unfortunately, realistic. Like Ruby, Lenny is forced to kill - in Ruby’s case the killing is accidental - while Lenny’s motivation is less apparent but equally believable.

I guess all this might make it sound distasteful, but it is not. The quality of writing lifts it from something sordid and makes you turn page after page. I didn’t think I’d like it, in fact I was prepared to hate it, but instead now that I’ve finished it I find myself looking at the other two books in the sequence with longing, wondering when I’m going to find time to read them. Like the characters in the book I too have succumbed to an addiction - but mine is of the literary kind.

Clare Dudman: Do you have any connection with snails?

Jake Arnott: I remember when I was young trying to catch a friend’s attention by throwing gravel at the window, and picking up a slug instead.

C.D: Have you ever had a life-changing event - if so what was it?

J.A: Most days seem to contain life-changing events - that’s how it should be I think. Probably the most important ones are the ones I can’t remember - like walking for the first time or saying my first word. But I can remember one early incident - the earliest I remember. My baby brother was crying about something and my mother tried to calm him down by saying, ‘Don’t worry it’s not the end of the world.’ And I remember it occurring to me that there could be an end. I must have been about four.

C.D: What is the saddest thing you’ve ever heard of or seen?

J.A: Lots of things. Some of them unrepeatable, heartbreaking.

C.D: What is happiness?

J.A: I don’t think happiness is something we can achieve. We can experience occasionally or fleetingly but yearning for happiness can cause unhappiness. I don’t think it can ever be a state of being. I feel quite strongly about that.

C.D: What is the first thing you do when you get up?

J.A: I get the porridge. I have a peculiar sort - a particular way of cooking it in a double boiler with no milk and sugar and not too much salt.

C.D: Do you have any connection with the north west?

Not much really except I used to got out with someone from Liverpool

About writing.

C.D: Have you always wanted to write?

J.A: In my mind. I didn’t always admit to it, I kept it quiet. Until I was published many people didn’t know I was at it.

C.D: How long did it take you to get your first novel published?

J.A: I was an overnight success after ten years of trying. Once I got an agent he sold it in a fortnight. Before that I’d had lots of stuff rejected.

C.D: Are you self-taught as a writer?

J.A: I prefer the term ‘self-learnt’. I try not to teach myself too much. I have given courses, but I’ve always said writing can’t be taught but it can be learnt.

C.D: What is your typical writing day?

J.A: I work until 5pm and then give up and hope that tomorrow will be better.

C.D: Why did you leave school at 16? You are obviously extremely bright. Why did you not stay on?

J.A: School and I didn’t get on. I couldn’t concentrate and I couldn’t fit in.

C.D: Do you think the great variety of jobs you had since has been beneficial to you as a writer?

J.A: Hard to say. I suspect that one day they will be useful. I have an anarchic c.v. and hope that one day all things will become useful.

C.D: Is there any one in particular that was useful?

J.A: Acting. I learnt the importance of finding a voice and hearing it in my head.

C.D: Was being arrested for suspicion of arson a pivotal moment?

J.A: It wasn’t so much losing my liberty as losing all my possessions. I lost everything. It was instant buddhism. It was useful in a way because it made me realise what is important. It made me realise how much we create problems and are stressed about things that are unimportant.

C.D: You seem to feel strongly about corruption in society in general and corruption in the police in particular. Do you think that the situation has changed recently? Is it getting better or worse?

J.A: I single out the police, but really nowhere in society is safe. We live in a corrupt world where everything is out of balance. It is hard not to be greedy and to resist corruption. We pretend we are immune that’s why we like seeing dramas where corruption is presented. As Shakespeare says in MEASURE FOR MEASURE ‘Some rise by sin, some by virtue fall.’ We quickly come to realise at an early age that being good doesn’t get us anywhere. Good deeds don’t go unpunished and the dirty scoundrels get on in the world. I explore that in my third book TRUECRIME - being good doesn’t get us anywhere.

About the THE LONG FIRM

C.D: I would say that THE LONG FIRM is not really a crime novel but a piece of fiction about a criminal. Would you agree? Have you any ideas about the difference?

J.A: Yes. I would call it historical fiction. It doesn’t follow the standard format of a crime novel.

C.D: Are the other two books HE KILLS COPPERS and TRUECRIME the same in structure?

J.A: Yes, they both contain different narratives.

C.D: How much of what is in your books is based on your life-experience?

J.A: Nothing is directly based. . It is all partly based on people I know at an emotional level. The emotional level is the important part. Also, sub-consciously, it is based on myself, I realise sometimes as I am writing that these things have somehow happened to me.

C.D: Were you happy with the result of the LONG FIRM as a TV adaptation?

J.A: YES!

C.D: Were you involved in the making? Or consulted at all?

J.A: I met with the people early on and kept up to speed. But really I let them get on with it. I was very happy with the writer, the producer, the director, the cast.

C.D: Did you ever go on set?

JA: Yes, much more glamorous than sitting at home writing.

C.D: Is there one voice in the LONG FIRM you liked writing more than the others?

J.A: Jack the Hat. He was furthest from me but he was the one I found came alive the most when I was writing him. He wrote himself.

C.D: Which voice was the most difficult?

J.A: (long pause) I think Terry. He was closest to me in character and was hardest to hear. It was difficult to distinguish his character from my own sometimes.

C.D: There is quite a lot of sex and violence in the novel, although it is no way gratuitous - given the topic, character and setting it is an essential piece. My final question then - given the topic of your talk is what is primarily your purpose when you write a violent scene. How do you go about imagining it? How do you go about making it so convincing?

JA: Gratuitous violence is unforgivable. I think it is important that people try to understand violence, its causes and effects. It is important to understand that it is not glamorous. It is a huge issue. We see violence portrayed as a firework we often don’t see where it has come from or its implications. It is too easy to portray. Real violence is messy, unchoreographed. It is difficult to tell what is happening in a fight.

Violence is ugly - implosive rather than explosive. What happens goes inside - in emotional, psychological and moral effects. It is claustrophobic.

I tend to avoid endless descriptions in my books. I like to use the threat of violence rather than describing actual scenes.

First I shall review THE LONG FIRM (which I do not think contains spoilers but the interview follows after the photograph).

THE LONG FIRM by Jake Arnott

THE LONG FIRM is about crime but is not really a crime novel, it could be accurately described as a character study of a man who happens to be a criminal - ‘A Torture Gang Boss’ in fact who lives alongside the Kray twins in 1960s London. The Kray twins are not the only nonfictional characters who take a bit-part in this book: others are Judy Garland, Dorothy Squires, Johhnnie Ray, Mickey Deans, all of them portrayed as washed up and unsavoury characters - sad people clinging onto life through a haze of drugs and alcohol.

THE LONG FIRM is about crime but is not really a crime novel, it could be accurately described as a character study of a man who happens to be a criminal - ‘A Torture Gang Boss’ in fact who lives alongside the Kray twins in 1960s London. The Kray twins are not the only nonfictional characters who take a bit-part in this book: others are Judy Garland, Dorothy Squires, Johhnnie Ray, Mickey Deans, all of them portrayed as washed up and unsavoury characters - sad people clinging onto life through a haze of drugs and alcohol.A large part of the adult life of Harry Starks is revealed through five people who are intimately involved with him: Terry, a young male prostitute and one-time boyfriend who escapes Starks’s clutches after being tortured with a red-hot poker in the mouth; another homosexual Lord Thursby who becomes involved in Starks’s dodgy business activities in a part of Africa; Jack the Hat, a heterosexual accomplice; Ruby a faded starlet who becomes Starks’s go-between with a corrupt policeman and finally Lenny who is a university lecturer and criminologist and is responsible for Starks’s interest in education once he is incarcerated in jail. Each of these people is corrupted by Starks, each one is tortured physically or mentally until they are forced to kill or torture others. Starks is charismatic, preys on those weaker than he is, which is just about everyone.

There is a lot of sex and violence in this novel. The first sex scene is on page seven. It is cursory, unemotional, it is only later on in the book that a couple of homosexual orgies are described in graphic detail. Starks is a homosexual (‘not gay’ he declares towards the end of the book) and one of the few things that disturbs him is the death of a young homosexual called Bernie. He is also Jewish, though this seems to have little bearing on his character, and a manic depressive - given to black periods when he retires to listen to recordings of Winston Churchill and punish the young men who love him. Harry Starks is overwhelmingly cruel and forces subjugation on anyone that comes close. The way he does this is convincing and extremely chilling.

Each of the characters in the novel has a distinctive voice. Terry’s is wheedling - unsurprising since he is in the middle of being physically abused. The Lord’s account is written in a diary form, which is quite pompous, while Jack the Hat’s is written in a fast-paced staccato. It is this voice I found the most sympathetic - Jack the Hat has motivation, some endearing qualities, weaknesses, a sense of guilt which were abjectly missing from any ot the other accounts. He is the one who doesn’t last. It is as if by showing weakness he condemns himself to an early death. Ruby’s account is written in a summarily fashion. She tells us how she feels about things rather than shows us; while Terry’s style is so full of jargon and correct-thinking it borders on the humorous and for a time is tongue in cheek - and I have to say I do know people who talk like that, so it is, unfortunately, realistic. Like Ruby, Lenny is forced to kill - in Ruby’s case the killing is accidental - while Lenny’s motivation is less apparent but equally believable.

I guess all this might make it sound distasteful, but it is not. The quality of writing lifts it from something sordid and makes you turn page after page. I didn’t think I’d like it, in fact I was prepared to hate it, but instead now that I’ve finished it I find myself looking at the other two books in the sequence with longing, wondering when I’m going to find time to read them. Like the characters in the book I too have succumbed to an addiction - but mine is of the literary kind.

Clare Dudman: Do you have any connection with snails?

Jake Arnott: I remember when I was young trying to catch a friend’s attention by throwing gravel at the window, and picking up a slug instead.

C.D: Have you ever had a life-changing event - if so what was it?

J.A: Most days seem to contain life-changing events - that’s how it should be I think. Probably the most important ones are the ones I can’t remember - like walking for the first time or saying my first word. But I can remember one early incident - the earliest I remember. My baby brother was crying about something and my mother tried to calm him down by saying, ‘Don’t worry it’s not the end of the world.’ And I remember it occurring to me that there could be an end. I must have been about four.

C.D: What is the saddest thing you’ve ever heard of or seen?

J.A: Lots of things. Some of them unrepeatable, heartbreaking.

C.D: What is happiness?

J.A: I don’t think happiness is something we can achieve. We can experience occasionally or fleetingly but yearning for happiness can cause unhappiness. I don’t think it can ever be a state of being. I feel quite strongly about that.

C.D: What is the first thing you do when you get up?

J.A: I get the porridge. I have a peculiar sort - a particular way of cooking it in a double boiler with no milk and sugar and not too much salt.

C.D: Do you have any connection with the north west?

Not much really except I used to got out with someone from Liverpool

About writing.

C.D: Have you always wanted to write?

J.A: In my mind. I didn’t always admit to it, I kept it quiet. Until I was published many people didn’t know I was at it.

C.D: How long did it take you to get your first novel published?

J.A: I was an overnight success after ten years of trying. Once I got an agent he sold it in a fortnight. Before that I’d had lots of stuff rejected.

C.D: Are you self-taught as a writer?

J.A: I prefer the term ‘self-learnt’. I try not to teach myself too much. I have given courses, but I’ve always said writing can’t be taught but it can be learnt.

C.D: What is your typical writing day?

J.A: I work until 5pm and then give up and hope that tomorrow will be better.

C.D: Why did you leave school at 16? You are obviously extremely bright. Why did you not stay on?

J.A: School and I didn’t get on. I couldn’t concentrate and I couldn’t fit in.

C.D: Do you think the great variety of jobs you had since has been beneficial to you as a writer?

J.A: Hard to say. I suspect that one day they will be useful. I have an anarchic c.v. and hope that one day all things will become useful.

C.D: Is there any one in particular that was useful?

J.A: Acting. I learnt the importance of finding a voice and hearing it in my head.

C.D: Was being arrested for suspicion of arson a pivotal moment?

J.A: It wasn’t so much losing my liberty as losing all my possessions. I lost everything. It was instant buddhism. It was useful in a way because it made me realise what is important. It made me realise how much we create problems and are stressed about things that are unimportant.

C.D: You seem to feel strongly about corruption in society in general and corruption in the police in particular. Do you think that the situation has changed recently? Is it getting better or worse?

J.A: I single out the police, but really nowhere in society is safe. We live in a corrupt world where everything is out of balance. It is hard not to be greedy and to resist corruption. We pretend we are immune that’s why we like seeing dramas where corruption is presented. As Shakespeare says in MEASURE FOR MEASURE ‘Some rise by sin, some by virtue fall.’ We quickly come to realise at an early age that being good doesn’t get us anywhere. Good deeds don’t go unpunished and the dirty scoundrels get on in the world. I explore that in my third book TRUECRIME - being good doesn’t get us anywhere.

About the THE LONG FIRM

C.D: I would say that THE LONG FIRM is not really a crime novel but a piece of fiction about a criminal. Would you agree? Have you any ideas about the difference?

J.A: Yes. I would call it historical fiction. It doesn’t follow the standard format of a crime novel.

C.D: Are the other two books HE KILLS COPPERS and TRUECRIME the same in structure?

J.A: Yes, they both contain different narratives.

C.D: How much of what is in your books is based on your life-experience?

J.A: Nothing is directly based. . It is all partly based on people I know at an emotional level. The emotional level is the important part. Also, sub-consciously, it is based on myself, I realise sometimes as I am writing that these things have somehow happened to me.

C.D: Were you happy with the result of the LONG FIRM as a TV adaptation?

J.A: YES!

C.D: Were you involved in the making? Or consulted at all?

J.A: I met with the people early on and kept up to speed. But really I let them get on with it. I was very happy with the writer, the producer, the director, the cast.

C.D: Did you ever go on set?

JA: Yes, much more glamorous than sitting at home writing.

C.D: Is there one voice in the LONG FIRM you liked writing more than the others?

J.A: Jack the Hat. He was furthest from me but he was the one I found came alive the most when I was writing him. He wrote himself.

C.D: Which voice was the most difficult?

J.A: (long pause) I think Terry. He was closest to me in character and was hardest to hear. It was difficult to distinguish his character from my own sometimes.

C.D: There is quite a lot of sex and violence in the novel, although it is no way gratuitous - given the topic, character and setting it is an essential piece. My final question then - given the topic of your talk is what is primarily your purpose when you write a violent scene. How do you go about imagining it? How do you go about making it so convincing?

JA: Gratuitous violence is unforgivable. I think it is important that people try to understand violence, its causes and effects. It is important to understand that it is not glamorous. It is a huge issue. We see violence portrayed as a firework we often don’t see where it has come from or its implications. It is too easy to portray. Real violence is messy, unchoreographed. It is difficult to tell what is happening in a fight.

Violence is ugly - implosive rather than explosive. What happens goes inside - in emotional, psychological and moral effects. It is claustrophobic.

I tend to avoid endless descriptions in my books. I like to use the threat of violence rather than describing actual scenes.

Interview with Sir David Frost

Interview took place on 4th October 2005 - the day that Ronnie Barker died.

Sir David Frost is going to be performing at the Chester Gateway on Tuesday 18th October and makes a plea for questions: the first half of his performance will be on his comedy and humour - with clips from the THAT WAS THE WEEK THAT WAS and THE FROST REPORT (including a tribute to the late Ronnie Barker); the second half will be a question and answer session and he is hoping to get a lot of good questions from the members of the audience. It will include anecdotes from his interviews which Sir David says is always a lot of fun.

SIR DAVID FROST

A quick google reveals that:

“He is the only person to have interviewed the last seven Presidents of the United States and the last six Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom”

(The Times)

His Nixon Interviews achieved “the largest audience for a news interview in history”

(New York Times).

So I interviewed him with some trepidation... However I have to say he was charming - a thoroughly good human being who, I believe, treats everyone with the same respect.

Clare Dudman: Do you have any connection with Chester or the north-west?

Sir David Frost: My connection with Chester is not as terrific as I would like, but my Uncle, the Reverend Kenneth Aldrich, had several very happy years as the Methodist Minister in Chester. So we heard a lot about Chester from him, and of course I’ve followed the somewhat roller coaster fortunes of Chester Football Club.

C.D: Have you ever had a life-changing event - if so what was it?

D.F: Going to Cambridge - I’d started writing shows for the local Methodist Youth Club already, but at Cambridge I was able to meet other people with similar ambitions and was very lucky to meet a fantastic range of people - Peter Cook, John Cleese, Ian McKellen, Derek Jacobi, Graeme Garden, Bill Odie - a tremendous cross-section of people together with future ministers including Ken Clarke and Michael Howard.

C. D: What is your proudest moment?

D F: There’s been a number: the birth of our three sons - very much so - then career-wise the response to the Nixon interviews in 1977, and this year I was given the BAFTA fellowship which is their highest honour.

C.D: Who was your favourite interviewee? The most devious? The most difficult?

D.F: Well, Nelson Mandela was certainly one of the most memorable, Baldur von Schirach, the former head of Hitler Youth was the most devious, the most difficult was ex King Ibn Sa’ad of Saudi Arabia because we had two interpreters, one for him and one for me and by the time I’d put the question my interpreter, who put it to his interpreter who put it to him and then he had responded to his interpreter who responded to my interpreter who responded to me you found you’d forgotten the question. Nowadays Gorbachov has a terrific simultaneous interpreter - if Gorbachov talks for just one minute the guy is so quick, after Gorbachov stops the interpreter only needs another 3 or 4 words to complete the minute.

C.D: That’s amazing.

D.F: Yes, amazing - that makes it much easier than with ex-King Ibn Sa’ad

C.D: Do you think that the TV interview has changed over the years? How?

D.F: I think it has - in the sense politicians have learnt how to deal with some sorts of questions, and then you have to play the game.. of chess, and learn how to challenge them again - that’s changing all the time. I think there are more pointless hectoring interviews. You only need to be an adversarial interviewer in an adversarial situation. When I was interviewing Nixon on the Watergate or the notorious swindler, Dr Emil Savundra then these had to be confrontational - but it is pointless to be confrontational otherwise. Confrontation tends to shut people up when the task is to draw them out.

C.D: Are American audiences different from British ones?

D.F: I don’t think American audiences are particularly different. I think because America is a nation of immigrants, whereas we are a nation of emigrants, I think Americans are particularly generous, perhaps more generous than we are in this country. I think the tastes are just the same; but with just two differences - one liner jokes is more prevalent in America, whereas the character comedy is more prevalent over here.

In politics - if you make one mistake, one big verbal mistake than your career will be over, but that doesn’t happen over here. As someone pointed ot - in Britain politicians stand for office; in America they run for office - which suggests a slightly more vigourous democracy.

C.D: What do you think THAT IS THE WEEK THAT WAS’s biggest legacy?

D.F: It opened the windows and let in the fresh air to television. Before we came along no one had ever done a sketch about the royal family, no one was allowed to make jokes about religion...Many producers said they were very grateful to THAT WAS THE WEEK THAT WAS because they could do much more after THAT WAS THE WEEK THAT WAS than they could do before it.

C.D: You were involved in SPITTING IMAGE as well weren’t you?

D.F: I was involved in SPITTING IMAGE but didn’t start it. The producer was John Lloyd who was brilliant, and the puppeteers were Fluck and Law. I was involved because I told John Lloyd that I thought we could get SPITTING IMAGE off the ground in America - if we had a whole story over half an hour instead of lots of little stories. So we did four or five which were successful.

C.D: What have you most enjoyed doing in your professional life?

D.F: I love comedy and the feeling of an audience’s laughter. This is true of all the well-known shows we’ve been talking about, but it’s also true of speeches too. I would say that I like to surf an audience (even though I’m not a swimmer so don’t even know how to surf), and their laughter.

C.D: What is happiness?

D.F: Happiness comes from doing the things you enjoy and, even more important, doing the things you believe in.

C.D: What is the saddest thing you’ve ever heard of or seen?

D.F: When I interviewed the then Prime Minister of Pakistan, Mr Bhutto, we went up to Murree, on the way to Islamabad, a high point in Pakistan and we stopped at a bridge, and down below there was a lorry below containing about 25 Pakistani soldiers that had crashed over the bridge - all dead, just to see them there was very sad.

C.D: At university you edited GRANTA (a literary magazine) - did you or do you ever write fiction?

D.F: Most of my books have been current affairs or humour, apart from a couple of short stories I wrote in Cambridge, I have never tried to write fiction, no. I’d like to try, I’ll get you to give me some lessons!

C.D: Are your writing anything at the moment?

D.F: I’m supposed to be writing the second volume of my memoirs. My first volume only went to the nineteen sixties and that came out in 1993. So I’m a bit slow getting out my second volume. My publishers are knocking on my door. I haven’t started yet.

C.D: What are your future plans?

D.F: I have a monthly Frost interview series coming out monthly on the BBC starting in November, and another series of through the keyhole, and then a new international show starting next year and also specials in America.

C.D: Finally any words on Ronnie Barker who died today?

D.F: He brightened the nation’s life and he certainly brightened mine. He was a superb sketch actor and a more serious actor too, but he was also of course a great writer. he wrote some of the best sketches ever written. He loved words - for instance the famous Dr Spooner who used to gets words wrong - he was fascinated by that and he wrote a series of sketches which were absolutely terrific. Things to do with words fascinated him - a brilliant writer and performer.

Sir David Frost is going to be performing at the Chester Gateway on Tuesday 18th October and makes a plea for questions: the first half of his performance will be on his comedy and humour - with clips from the THAT WAS THE WEEK THAT WAS and THE FROST REPORT (including a tribute to the late Ronnie Barker); the second half will be a question and answer session and he is hoping to get a lot of good questions from the members of the audience. It will include anecdotes from his interviews which Sir David says is always a lot of fun.

SIR DAVID FROST

A quick google reveals that:

“He is the only person to have interviewed the last seven Presidents of the United States and the last six Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom”

(The Times)

His Nixon Interviews achieved “the largest audience for a news interview in history”

(New York Times).

So I interviewed him with some trepidation... However I have to say he was charming - a thoroughly good human being who, I believe, treats everyone with the same respect.

Clare Dudman: Do you have any connection with Chester or the north-west?

Sir David Frost: My connection with Chester is not as terrific as I would like, but my Uncle, the Reverend Kenneth Aldrich, had several very happy years as the Methodist Minister in Chester. So we heard a lot about Chester from him, and of course I’ve followed the somewhat roller coaster fortunes of Chester Football Club.

C.D: Have you ever had a life-changing event - if so what was it?

D.F: Going to Cambridge - I’d started writing shows for the local Methodist Youth Club already, but at Cambridge I was able to meet other people with similar ambitions and was very lucky to meet a fantastic range of people - Peter Cook, John Cleese, Ian McKellen, Derek Jacobi, Graeme Garden, Bill Odie - a tremendous cross-section of people together with future ministers including Ken Clarke and Michael Howard.

C. D: What is your proudest moment?

D F: There’s been a number: the birth of our three sons - very much so - then career-wise the response to the Nixon interviews in 1977, and this year I was given the BAFTA fellowship which is their highest honour.

C.D: Who was your favourite interviewee? The most devious? The most difficult?

D.F: Well, Nelson Mandela was certainly one of the most memorable, Baldur von Schirach, the former head of Hitler Youth was the most devious, the most difficult was ex King Ibn Sa’ad of Saudi Arabia because we had two interpreters, one for him and one for me and by the time I’d put the question my interpreter, who put it to his interpreter who put it to him and then he had responded to his interpreter who responded to my interpreter who responded to me you found you’d forgotten the question. Nowadays Gorbachov has a terrific simultaneous interpreter - if Gorbachov talks for just one minute the guy is so quick, after Gorbachov stops the interpreter only needs another 3 or 4 words to complete the minute.

C.D: That’s amazing.

D.F: Yes, amazing - that makes it much easier than with ex-King Ibn Sa’ad

C.D: Do you think that the TV interview has changed over the years? How?

D.F: I think it has - in the sense politicians have learnt how to deal with some sorts of questions, and then you have to play the game.. of chess, and learn how to challenge them again - that’s changing all the time. I think there are more pointless hectoring interviews. You only need to be an adversarial interviewer in an adversarial situation. When I was interviewing Nixon on the Watergate or the notorious swindler, Dr Emil Savundra then these had to be confrontational - but it is pointless to be confrontational otherwise. Confrontation tends to shut people up when the task is to draw them out.

C.D: Are American audiences different from British ones?

D.F: I don’t think American audiences are particularly different. I think because America is a nation of immigrants, whereas we are a nation of emigrants, I think Americans are particularly generous, perhaps more generous than we are in this country. I think the tastes are just the same; but with just two differences - one liner jokes is more prevalent in America, whereas the character comedy is more prevalent over here.

In politics - if you make one mistake, one big verbal mistake than your career will be over, but that doesn’t happen over here. As someone pointed ot - in Britain politicians stand for office; in America they run for office - which suggests a slightly more vigourous democracy.

C.D: What do you think THAT IS THE WEEK THAT WAS’s biggest legacy?

D.F: It opened the windows and let in the fresh air to television. Before we came along no one had ever done a sketch about the royal family, no one was allowed to make jokes about religion...Many producers said they were very grateful to THAT WAS THE WEEK THAT WAS because they could do much more after THAT WAS THE WEEK THAT WAS than they could do before it.

C.D: You were involved in SPITTING IMAGE as well weren’t you?

D.F: I was involved in SPITTING IMAGE but didn’t start it. The producer was John Lloyd who was brilliant, and the puppeteers were Fluck and Law. I was involved because I told John Lloyd that I thought we could get SPITTING IMAGE off the ground in America - if we had a whole story over half an hour instead of lots of little stories. So we did four or five which were successful.

C.D: What have you most enjoyed doing in your professional life?

D.F: I love comedy and the feeling of an audience’s laughter. This is true of all the well-known shows we’ve been talking about, but it’s also true of speeches too. I would say that I like to surf an audience (even though I’m not a swimmer so don’t even know how to surf), and their laughter.

C.D: What is happiness?

D.F: Happiness comes from doing the things you enjoy and, even more important, doing the things you believe in.

C.D: What is the saddest thing you’ve ever heard of or seen?

D.F: When I interviewed the then Prime Minister of Pakistan, Mr Bhutto, we went up to Murree, on the way to Islamabad, a high point in Pakistan and we stopped at a bridge, and down below there was a lorry below containing about 25 Pakistani soldiers that had crashed over the bridge - all dead, just to see them there was very sad.

C.D: At university you edited GRANTA (a literary magazine) - did you or do you ever write fiction?

D.F: Most of my books have been current affairs or humour, apart from a couple of short stories I wrote in Cambridge, I have never tried to write fiction, no. I’d like to try, I’ll get you to give me some lessons!

C.D: Are your writing anything at the moment?

D.F: I’m supposed to be writing the second volume of my memoirs. My first volume only went to the nineteen sixties and that came out in 1993. So I’m a bit slow getting out my second volume. My publishers are knocking on my door. I haven’t started yet.

C.D: What are your future plans?

D.F: I have a monthly Frost interview series coming out monthly on the BBC starting in November, and another series of through the keyhole, and then a new international show starting next year and also specials in America.

C.D: Finally any words on Ronnie Barker who died today?

D.F: He brightened the nation’s life and he certainly brightened mine. He was a superb sketch actor and a more serious actor too, but he was also of course a great writer. he wrote some of the best sketches ever written. He loved words - for instance the famous Dr Spooner who used to gets words wrong - he was fascinated by that and he wrote a series of sketches which were absolutely terrific. Things to do with words fascinated him - a brilliant writer and performer.

Wednesday, October 12, 2005

The Cheltenham Literature Festival

My Cheltenham Literature Festival class seemed to go quite well - twelve keen writers eager to improve their dialogue. Since this is a topic I have always found quite difficult I had quite a lot to say on the subject - I think it is easier to teach something you yourself have found quite hard to learn. I've heard that some writers actually hear their characters’ voices talking to them but find descriptions more difficult - while others are more visual writers and I am sure I am in the last camp.

My Cheltenham Literature Festival class seemed to go quite well - twelve keen writers eager to improve their dialogue. Since this is a topic I have always found quite difficult I had quite a lot to say on the subject - I think it is easier to teach something you yourself have found quite hard to learn. I've heard that some writers actually hear their characters’ voices talking to them but find descriptions more difficult - while others are more visual writers and I am sure I am in the last camp.  The Cheltenham Literature Festival looks after its guests very well. At the station was a volunteer holding a sign with 'Cheltenham Literature Festival Guest' and I realised then that that was some unrealised ambition of mine - to be met by someone with a sign...I was supposed to be sharing a ride with Alison Weir but her train was delayed so I was whisked off to my hotel alone with a reminder to go on to the town hall later. The hotel turned out to be one of those small quiet ones, backing onto a park, with a pretty back garden and friendly owners.

The Cheltenham Literature Festival looks after its guests very well. At the station was a volunteer holding a sign with 'Cheltenham Literature Festival Guest' and I realised then that that was some unrealised ambition of mine - to be met by someone with a sign...I was supposed to be sharing a ride with Alison Weir but her train was delayed so I was whisked off to my hotel alone with a reminder to go on to the town hall later. The hotel turned out to be one of those small quiet ones, backing onto a park, with a pretty back garden and friendly owners. The town hall was about ten minutes away, clearly visible with banners advertising the festival all along the street and then lots more banners and flags outside the building itself -even I couldn't miss it. Inside I was given instructions to go to somewhere called THE WRITERS ROOM.

This turned out to be a small room with a bar in one corner, a table laid out with salad and fruit and a couple of drinks urns. There were a few people sitting around tables talking and at first I felt like I was intruding into some private club. There was a man sitting in a wicker chair I vaguely recognised from a television news programme. This time I managed to stop myself smiling at him as if I knew him. This is a mistake I've made before. The TV screen is one way, I reminded myself - he looks out at me, but he can't see me looking back. So I helped myself to some food as instructed in my Cheltenham Literature Festival letter and sat at my own at one of the tables hoping someone would talk to me - but of course no one did.

Eventually I accosted an innocent author also sitting on his own who turned out to be the military historian and ex-Observer journalist Colin Smith who was very interesting and he told me where to get 'my performer pass'. This takes the form of a green armband which is much better than the piece of card I was expecting - although I have to say that the idea of me being any sort of performer is pretty funny...I also had a word with the author Andrew Taylor (who had taken a similar class that morning and is going to be a feature of a future blog).

Eventually I accosted an innocent author also sitting on his own who turned out to be the military historian and ex-Observer journalist Colin Smith who was very interesting and he told me where to get 'my performer pass'. This takes the form of a green armband which is much better than the piece of card I was expecting - although I have to say that the idea of me being any sort of performer is pretty funny...I also had a word with the author Andrew Taylor (who had taken a similar class that morning and is going to be a feature of a future blog).A young and very charming helper in a black T-shirt then came up to me and introduced herself - Jasmine - she showed me to my venue - a room at the back of St Andrews Church, checked that everything was working and helped me rearrange the desks in the room.

She has just finished her education at the very famous and exclusive Cheltenham Ladies College, which was just next door.

We got through many examples of dialogue - and my 'students' produced some fine examples of their own. Then, passing by a man from Ottakars forlornly not selling copies of my books (he looked quite embarrassed, and I paused for moment wondering if I should offer to sign any, but decided against it) went on to the Festival tent...

...to listen to Lawrence Sail, Helen Dunmore and Bernard O’Donoghue read out their own and other people’s poetry from an new poetry anthology LIGHT UNLOCKED

which is a beautiful little book nearly each poem illustrated with an engraving by John Lawrence. Since there some of my favourite poets in here (viz Gillian Clarke, Wendy Cope, U.A. Fanthorpe, Benjamin Zephaniah and Seamus Heaney) I bought a copy. I think I am going to use it as an poet autograph book.

which is a beautiful little book nearly each poem illustrated with an engraving by John Lawrence. Since there some of my favourite poets in here (viz Gillian Clarke, Wendy Cope, U.A. Fanthorpe, Benjamin Zephaniah and Seamus Heaney) I bought a copy. I think I am going to use it as an poet autograph book. The tent is really a big extension of Ottakars’s bookshop and some of my books were on display just like all the rest - so I was pleased. Apart from the bookshop area there was a small stage and screened off theatre. A covered walkway leads to the town hall where I was very lucky to be able to see Alan Bennett read and speak to a packed audience. Towards the end he appealed to the audience to buy books from INDEPENDENT BOOKSELLERS rather than chains (e.g. Waterstones) because their 3 for 2 offer has resulted in many bookshops being unable to compete and consequently going out of business.

This was followed by an illustrated talk by the geographer Nick Middleton on his book EXTREMES ALONG THE SILK ROAD which was fascinating, especially the section about an island called Voz in the Aral Sea where there has been extensive experimentation with biological warfare agents by the Russians. It sounded frightening and I wanted to learn more. I wanted to know what they did, how exactly do you experiment with biological warfare agents? What is there to test? The microbes kill - what more is there to know? Maybe they try tried to make the microbes more hardy or more potent. Apart from this the Soviet regime had also drained the 'sea' (which used to be the world's fourth largest lake) - and there were impressive and depressing pictures of great hulks of beached trawlers, presumably representing ruined lives and a way of life now gone forever.

This was followed by an illustrated talk by the geographer Nick Middleton on his book EXTREMES ALONG THE SILK ROAD which was fascinating, especially the section about an island called Voz in the Aral Sea where there has been extensive experimentation with biological warfare agents by the Russians. It sounded frightening and I wanted to learn more. I wanted to know what they did, how exactly do you experiment with biological warfare agents? What is there to test? The microbes kill - what more is there to know? Maybe they try tried to make the microbes more hardy or more potent. Apart from this the Soviet regime had also drained the 'sea' (which used to be the world's fourth largest lake) - and there were impressive and depressing pictures of great hulks of beached trawlers, presumably representing ruined lives and a way of life now gone forever. Back in the WRITERS ROOM things were becoming even more hospitable with the happy sound of corks being extracted from wine bottles and I spent an enjoyable few minutes talking to Michael Buerk about the joys of living in the north west of England before he was irritatingly removed to the stage (after I had been ushered to a reserved seat in front of a large hushed audience). His discussion on life as a BBC war reporter with Rageh Omaar (who still doesn’t look old enough to be out of school never mind reporting from war zones) about being a BBC war reporter was very interesting. According to Mr Omaar part of the BBC pre-visit safety training course before going off into a war zone involves testing for the presence of land mines with a biro.

Saturday, October 08, 2005

Book Search at Basingstoke.

Here is the window display at Ottakars in Basingstoke promoting WORDFEST. On the way to the Willis Museum I went inside hoping to find a copy of my book - subject of my talk at the museum today - but there was not one copy. I had a word with the manager but apparently they do not stock all books for the festival since there are too many. When I got home looked through the programme and did a quick count - 20 recently published books (at most) are featured.

My book was not in Waterstones either. Less than six months after it came out in paperback my book is nowhere to be seen. This is disappointing.

However my talk at the Willis went well with lots of interesting questions, and a very good ploughmans lunch prepared for the customers by staff at the museum which was much appreciated...and I sold a few of the books I'd brought with me on the eight hour return train journey.

Friday, October 07, 2005

WordFest at Basingstoke

Tomorrow I am going to the Willis Museum in Basingstoke to give a lunchtime talk on the 'Diagnosis and Misdiagnosis of Insanity in the Nineteenth Century'. There is a review of a similar talk I gave as part of the Swindon Literature Festival by Ben Payne in the Swindon Evening Advertiser which I think is pretty funny.

Tomorrow I am going to the Willis Museum in Basingstoke to give a lunchtime talk on the 'Diagnosis and Misdiagnosis of Insanity in the Nineteenth Century'. There is a review of a similar talk I gave as part of the Swindon Literature Festival by Ben Payne in the Swindon Evening Advertiser which I think is pretty funny.

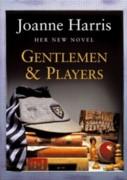

GENTLEMEN AND PLAYERS and an interview with Joanne Harris.

On October 11th Joanne Harris, one of Britain's most successful novelists, is coming to the Chester Literature Festival to read from her latest work GENTLEMEN AND PLAYERS and to answer questions about her work. As a little advance publicity for the event Joanne Harris kindly agreed to be interviewed. The interview follows beneath her photograph below but first a review of the book.

GENTLEMEN AND PLAYERS: A Review.

GENTLEMEN AND PLAYERS: A Review.

One of the last passages in this book made me smile: it describes a conversation between a newly qualified teacher who has aspirations to be a writer and a teacher about to embark on his hundredth term '...nothing good ever comes of a teacher turned scribbler...' says the old hand. This must be Joanne Harris teasing her readers - this teacher turned scribbler has, in fact, come to much good - shortlisted for the Whitbread novel of the year with CHOCOLAT, long-listed for the Orange Prize for fiction with FIVE QUARTERS OF THE ORANGE and three of her novels reaching number 1 in the Sunday Times best-seller lists - clearly being a ‘scribbler’ has served ex-teacher Joanne Harris very well indeed.

The book is about revenge set in an independent school for boys and told in two different voices - the voice of Roy Straitley a Latin master who is coming up to his 100th term at St Oswalds and the mystery voice which we know from the start is one of the new teachers, has long associations with the school and is set on revenge. Part of the fun of the book is guessing the identity of this voice - the ‘mole’. As the events become more and more sinister the suspicions change. There is something about the book that is slightly reminiscent of Donna Tartt’s THE SECRET HISTORY, although it is more light-hearted and funny.